Neonatal intubation

exp date isn't null, but text field is

Objectives

This guideline is applicable to neonatal unit staff in West of Scotland Neonatal units. It should be used with reference to the relevant pharmacy monographs. It covers:

- Rationale & Background

- Video Laryngoscopy

- Pre-Medication

- Preparation

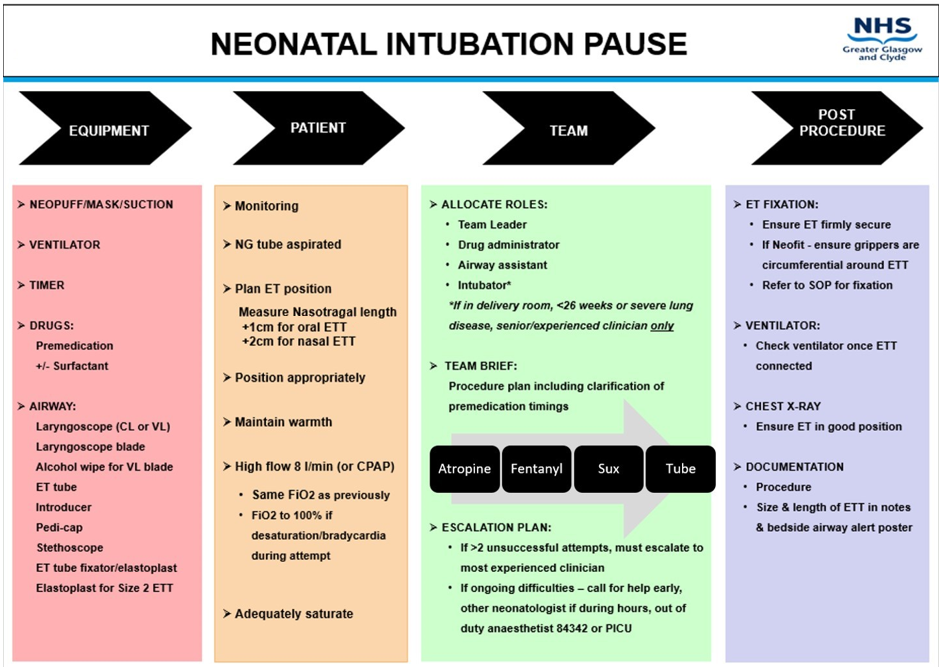

- Intubation Pause

- Procedure

- Trouble Shooting

- Appendix 1 – Intubation Pause

- Appendix 2 – Intubation video examples

Neonatal tracheal intubation is required for a number of reasons including airway management, surfactant administration and assisting ventilation in respiratory insufficiency.

Following assessment of the infant and decision to proceed with intubation, a structured and safe approach should be taken, as covered in this guideline. The procedure has the potential to provoke marked physiological changes and should never be undertaken lightly1-3. In addition to potential cardio-respiratory instability, there are significant complications that may arise from trauma to the tissues, including potential to cause perforation of the pharynx, oesophagus or trachea.

Intubation requires staff who are skilled in the management of the infant airway, generally an experienced middle grade doctor, suitably experienced ANNP and/or a consultant. With a move towards non-invasive ventilation over recent years, there are fewer opportunities to perform neonatal intubation, and gaining adequate experience is a challenge for paediatric and neonatal trainees. Introduction of the video laryngoscope in the West of Scotland has been an excellent tool to facilitate intubation education and training and will be covered in this guideline.

Intubations should always be performed with senior supervision. Special consideration and escalation planning should be undertaken taken if there has been a previous difficult intubation, or if there is a suspected airway abnormality or congenital anomaly of the head or neck. Please refer to the difficult airway guideline.

Although intubation is an important method of establishing an airway, simpler methods including a correctly applied face mask or laryngeal mask airway. These are sufficient in the majority of infants requiring resuscitation and certainly until senior help arrives in those needing prolonged ventilation.

Video laryngoscopy (VL) is being increasingly used in neonatal endotracheal intubation. Junior intubation success rates have been shown to be superior if their supervisor can share their view on a VL screen and guide the attempt in real time.4 The magnified airway view provided on the screen can also be beneficial for intubation of infants with potentially difficult airways4,5.

The currently available video laryngoscope blades have differences compared with conventional laryngoscope blades6. This is particularly relevant when using the video laryngoscope to obtain a direct airway view.

Newer brands of VL now available include CMAC (Storz) and Glidescope Core and Go with Miller blades (Verathon). The Glidescope Core and Go show promise as their blades more closely resemble traditional blades and are disposable. However they do not make a 00 blade and are big to use in babies less than 1000g. The CMAC’s smallest blade is the 0 but they have moved the position of the light so that it is usable in very small babies.

VL is most useful when used by novice intubators supervised by senior colleagues therefore requires the presence of an experienced intubator.

Intubation is a painful & uncomfortable procedure1-3. Premedication makes the procedure easier, safer and better tolerated by the baby. It provides analgesia and facilitates smoother passage of the ET tube by allowing jaw relaxation, opening and immobilising the vocal cords, and by preventing coughing, gagging or diaphragmatic movements3.

A combination of a sedative and muscle relaxant has been shown to shorten time to successful intubation and lessen the physiological unwanted effects. Intubation without drugs is associated with hypoxia, vagal bradycardia and hypertension, with secondary effects on intracerebral perfusion.

Premedication can be used for the majority of elective and emergency intubations on the neonatal unit. Caution should be used if there are concerns about airway obstruction and there should first be a discussion with the consultant. Tracheal intubation without the use of premedication should only be considered in the delivery room or emergency life-threatening situations where IV access is not available3.

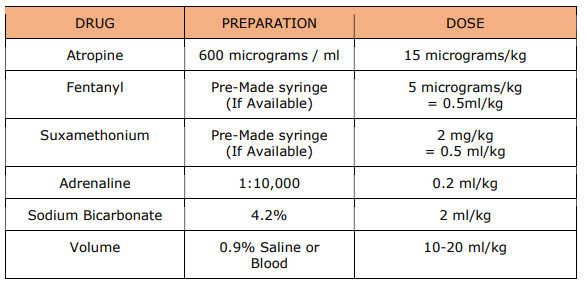

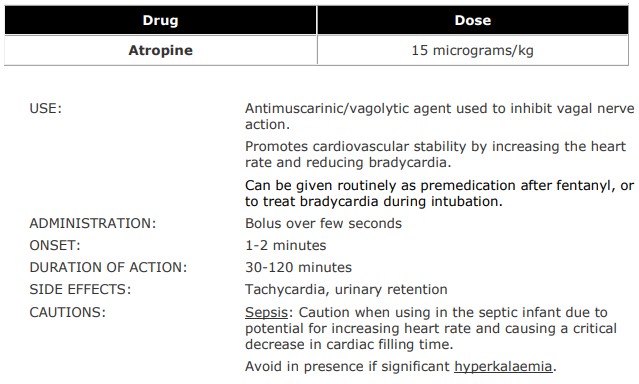

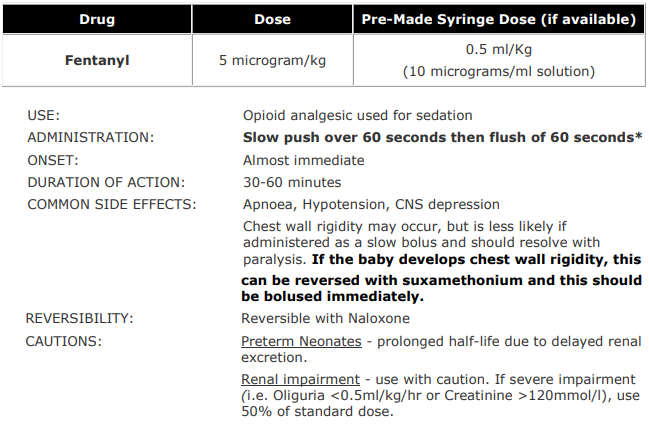

While the evidence regarding the best combination of sedative and muscle relaxant is lacking, the regime detailed in this document has the most evidence in the preterm and newborn population2,7-9. Routine practice in the West of Scotland involves the use of fentanyl and suxamethonium. Fentanyl has been widely used in neonates for some time and is the recommended analgesic for intubations. Morphine should only be used if there are no other alternatives. Suxamethonium is the preferred paralytic agent due to its rapid onset and short duration of action. Atropine is an antimuscarinic agent that helps to prevent reflex bradycardia and instability as a result of exaggerated vagal response during laryngoscopy. Atropine should be given routinely as part of pre-medication in order to promote cardiovascular stability.

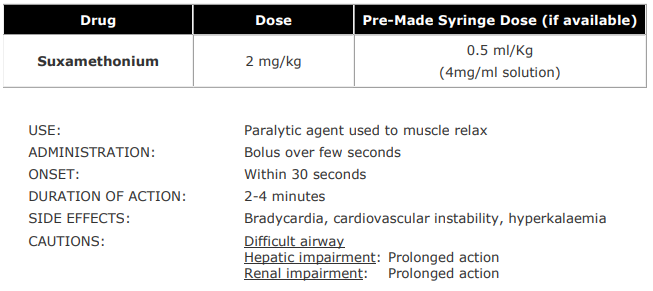

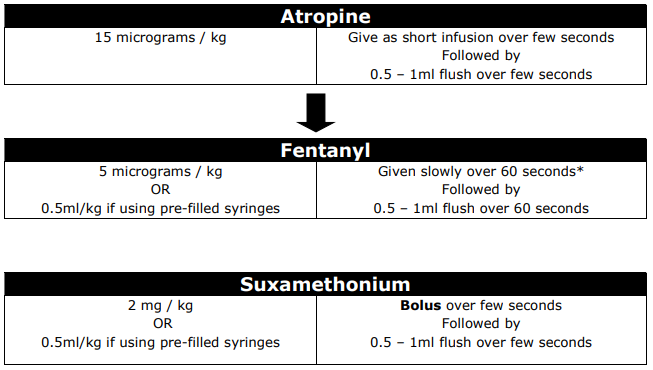

In order to shorten time of drug preparation and improve safety, pre-made packs with standardised dosing of fentanyl and suxamethonium are available. Due to the mechanism of action and potential side effects of the drugs, the order and timing of administration is important. All drugs must be drawn up and checked before the first one is given. If giving atropine routinely as premedication, it can be given first. The fentanyl is then given slowly to avoid side effects of chest wall rigidity, followed by suxamethonium. Further details below.

All staff giving premedication must be familiar with the correct administration procedures and the team leader must ensure this prior to starting.

There may be situations where an alternative drug may be indicated e.g. ketamine as a sedative in cardiac cases. The appropriate drug should be discussed with the on call consultant and/or speciality team involved.

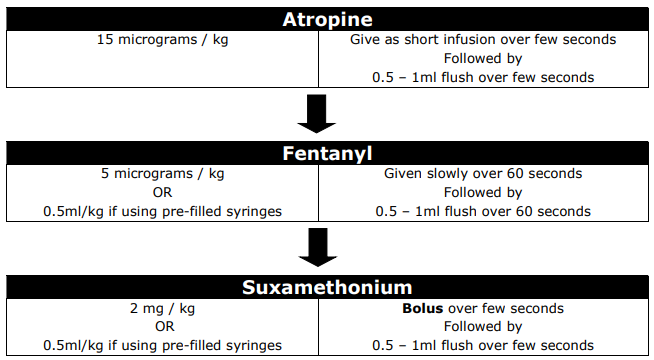

ATROPINE

FENTANYL

SUXAMETHONIUM

ADMINISTRATION OF PRE-MEDICATION

*In the previous version of this guideline, a suggested bolus time for fentanyl of 3 minutes was introduced. There are no studies to support that this was an optimal time. It was introduced to discourage fentanyl being given as a fast bolus. In this updated version, we still want fentanyl to be given slowly but have reduced the suggested bolus time from 3 minutes to 1 minute. This is because we are now recommending using high flow or CPAP/DuoPAP during intubation attempts and aiming to avoid the need for routine mask IPPV before an intubation attempt. High Flow (or CPAP/DuoPAP) delivered to the baby during an attempt promotes physiological stability and increases first attempt success rate.10 Fentanyl given slowly over 60secs followed by a slow flush reduces the apnoea time before the attempt and reduces the need for IPPV before the intubation attempt while is still slow enough to cause a low incidence of chest wall rigidity. Chest wall rigidity has been reported in slow infusions as well as fast blouses. If suspected, the suxamethonium should be bolused quickly as this reverses the chest wall rigidity.

Before every intubation, it is important to consider:

- Choice of Intubator

- Escalation Planning

- ET size & length

- Apnoeic Oxygenation

Choice of Intubator

As intubations are increasingly uncommon occurrences, it is essential that consultants and senior trainees gain the appropriate experience to achieve and maintain skills and confidence. Anaesthetic literature suggests that >40 intubations are required to achieve competency10. It is essential that future neonatologists and consultants are given priority to allow them to hone and maintain this essential skill. If the senior clinicians available feel competent, then more junior clinicians can attempt to intubate. It is important that prior to every intubation, careful consideration is given to the choice of intubator on an individual case basis. This will depend on a number of factors including the baby, skill set of the team, and clinical setting.

Delivery Room Intubations

With a move away from intubation at birth, even in the most preterm babies, delivery room intubations are far less common. This is a stressful setting for intubation, with lower success rates, particularly for more junior and inexperienced trainees. Unsuccessful intubation attempts early in a clinicians intubating career are very stressful and prolong their time to competency.12 Unsuccessful attempts can have serious consequences for the infant and increase very preterm infants’ risk of IVH13. Trainees’ first intubation attempts should therefore not be at delivery. It is recommended that delivery room intubations should be performed by an experienced member of the team with several previous successful intubations, i.e. senior trainees and ANNPs, or consultants.

NICU Intubations

NICU intubations are often performed in a more controlled manner. If deemed appropriate, junior clinicians can attempt to intubate under direct supervision, ideally with a video laryngoscope. Success rates with a VL are higher for all grade of intubator, and the difference between intubation success with the VL and the CL is largest in junior trainees. Infants with severe lung disease or ex-preterm infants with severe chronic lung disease will often decompensate quickly after pre-medications and are therefore not generally suitable for inexperienced intubators.

Escalation Planning

A clear escalation plan must be agreed by the team prior to intubation, and specific to each individual unit. Most junior clinicians (trainees and some ANNPs) will not have the experience deemed to be competent or comfortable performing intubations unsupervised. It is vital that they seek senior support before undertaking intubation. They should be aware that effective face mask ventilation and alternative airway adjuncts, for example a laryngeal mask, can provide a temporary secure airway until a more senior clinician arrives. A junior clinician should be given the opportunity to perform intubation in the appropriate setting, with a maximum of two attempts. By the third attempt, the intubator should be the most experienced person within the team. No clinician should continue with repeated attempts if initial attempts are unsuccessful. Risk of adverse events increase with each attempt and are almost then times more likely is three or more attempts occur. Each attempt should be limited to approximately 30-60 seconds, and only while cardiorespiratory stability is maintained. After each unsuccessful attempt, the baby should be stabilised with mask ventilation.

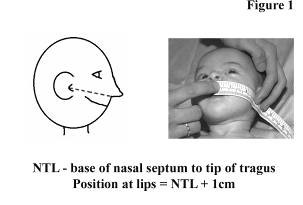

ET size & length

Guide for Endotracheal Tube Length

|

Measure the naso-tragal length from the base of nasal septum to tragus, and add:-

|

|

Guide for Endotracheal Tube Size

|

Weight (grams) |

ET Tube Size (Diameter in mm) |

|

<1000 |

2.5 |

|

1000-1900 |

3.0 |

|

1900-3700 |

3.5 |

|

>3700 |

4.0 |

If the baby’s weight is not known, the following table can be used to predict the correct size ET tube:

|

Gestation (weeks) |

ET Tube Size (Diameter in mm) |

|

<28 |

2.5 |

|

28-34 |

3.0 |

|

34 – Term |

3.5 |

|

Term+ |

4.0 |

When the team are ready to begin the procedure should be carried out in the following order:

- Set the Scene

- Intubation pause

- Patient optimisation

- Pre-medication

- Laryngoscopy

- Confirmation of ET tube placement & secure

- Post procedure management

1. SET THE SCENE

Choice of Intubator

- See above

Audience

- When first learning to intubate, a large audience (especially parents or multiple senior colleagues) reported to increase the stressfulness of the situation

- The novice intubator may not have the confidence to ask to reduce the audience but their instructor does

Reassure

- This is commonly reported to be a stressful situation for a novice intubator

- They may appreciate being reminded that the child is in safe hands and that the overall clinical care of the infant is the responsibility of their supervisor not them. They will be told to stop the attempt if the baby is desaturating etc, they do not need to worry about the infant’s numbers, the duration of the attempt etc.

2. INTUBATION PAUSE

The intubation pause is a planning and safety prompt to help prepare the team and the baby for intubation. It is a structured checklist designed to enhance organisation and team communication, and ensure intubation is carried out as safely and controlled as possible. It should be attached to all airway trolleys and performed before every intubation, where time allows.

3. OPTIMISE PATIENT

A recent RCT has shown improved intubation success rates and less physiological instability if the baby is on high flow during the intubation attempt, NNT=7.10 As this is a safe, reasonably straightforward intervention that improves intubation safety and success, we aim to implement it as the standard of care. The baby would be placed on 8l/min of high flow on the same oxygen they were on before the attempt. If they desaturate during the attempt to <80%, the oxygen is turned up to 100%.

Some consideration needs to be given before the intubation attempt how to deliver this to the infant. If the baby is already on high flow via vapotherm before the intubation, then it is reasonable for them to stay on it during the attempt and have a separate ventilator set up. If the baby is already on high flow delivered by a ventilator (either SLE or Fabian), it is reasonable for them to be left on it until intubated then change the circuit on the ventilator and change to ventilation. If the baby is on CPAP or DuoPAP, it could be considered to use these as the form of respiratory support during the intubation attempt. However if in this case, the CPAP/DuoPAP on the baby’s face can make it more challenging obtain a view performing direct laryngoscopy, less of an issue with VL.

The other challenge is performing mask IPPV if so required. The rate of administration of the fentanyl is now 60seconds with a 30 second flush. This is still slow enough to have a low incidence of chest wall rigidity but fast enough so that routine IPPV before attempts should not be required. If IPPV is required either before or during attempts, the high flow or CPAP needs to be removed so that a seal can be obtained with a facemask, then replaced again for the next attempt.

4. PRE-MEDICATION

5. LARYNGOSCOPY & ET TUBE INSERTION

- Holding laryngoscope in the left hand, use right hand to open the mouth wide (premedication can cause some spasm that may need to be overcome)

- Gently insert the blade to push the tongue to the left and the advance towards the throat

- Use the uvula to help maintain position in the midline, if uvula not in the midline, reposition, the scope is usually heading to left

- Advance the blade forward gently

- Lift laryngoscope handle in a forward and upward motion

- Avoid a levering action against the top gum

- Instructors hand on the infants neck can feel the blade tip (to help guide if the scope is too far in or not far enough)

- Cricoid pressure can be applied using the little finger of the left hand, or by an assistant (care should be taken not to exert excessive pressure)

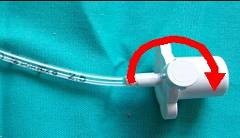

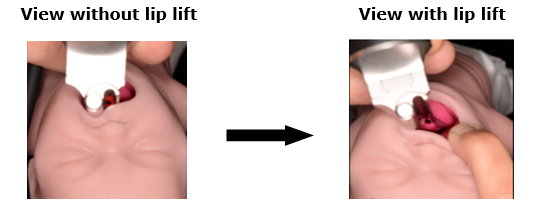

- With the video laryngoscope, an airway assistant may also lift the top lip of the infant to allow more space if obtaining a direct airway view and to allow more space for insertion of the ET tube in the mouth, as shown below:

- Use suction only if secretions are impairing view

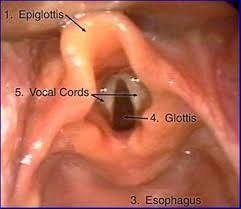

- Bring the posterior larynx and vocal cords into view, as shown below:

- Hold the tube high up and with the natural slope facing forward, as it is easier to direct

- Feed the tube in from the side to allow visualisation of it passing through the cords

- Use the black marker near the tip of the tube as a guide to depth of insertion initially

- Adjust to previously measured naso-tragal +1cm measurement

- Be cautious as to how far to insert the tube as it is often to far in

- Secure the ETT tube against the roof of palate or firmly at the lips

- Carefully remove laryngoscope and introducer (if used)

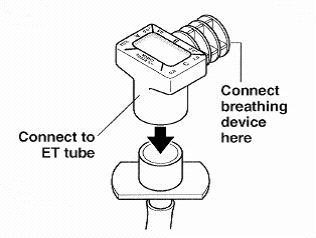

- Connect CO2 detector and ventilation circuit to confirm correct ETT position (see below)

- Secure ET with an appropriate fixation device, ensuring a good seal to the skin and avoiding traction on the ETT

- Provide IPPV once ET position confirmed and throughout securing process

- Attach ETT to ventilator and adjust settings as required

- Move infant back into position carefully, ensuring ET is secure when moving infant and using a 2 person technique to avoid accidental extubation

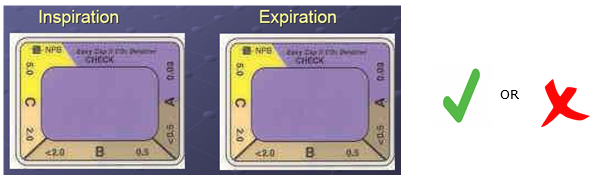

6. CONFIRMING ET TUBE PLACEMENT

End-tidal CO2 monitoring is recommended to allow immediate confirmation of a correctly positioned ET tube. This can be achieved with a colorimetric device or a side stream CO2 monitor 14,15. The most widely used device in the West of Scotland is Pedi-cap. Pedi-cap is a non-toxic chemical indicator which rapidly responds to exhaled CO2 with a simple colour change of purple to gold. It is easily attached to the ET tube and breathing device and the result should be interpreted following 6 positive pressure breaths.

As end-tidal CO2 is a reflection of ventilation, cardiac output, pulmonary blood flow and metabolism, false negative results may be seen. The response may be delayed, equivocal or absent in a number of situations including:

- ET tube in right main bronchus

- Extremely low birth weight or preterm infants

- Babies with poor perfusion or in cardiac arrest

- Reduced pulmonary blood flow (e.g. cardiac anomalies)

- Severe airway obstruction (e.g. meconium aspiration)

False positive results may also be seen in contamination with gastric contents and drugs including adrenaline.

Tracheal Intubation: Purple to gold

Oesophageal Intubation: Purple to beige

Possible Tracheal Intubation

In cases of poor or absent pulmonary blood flow and/or cardiac output, no colour change or a delay in colour change may be seen initially.

If confident in ETT placement, ensure the ET length is correct. The VL is useful in this scenario where the team can visualise the tube placement. If no Pedi-cap response, consider increasing the PIP and FiO2, while assessing other physiological indicators of appropriate ET position11, including:

- Increase in heart rate (the best physiological indicator of adequate ventilation)

- Effective chest wall movement

- Misting of the ETT on expiration

- Maintenance or improvement in the oxygen saturation (N.B. improvement in oxygenation may be slow in the presence of pulmonary hypertension)

- Equal air entry on both sides of the chest

If none of the above indicators are present, it is important to consider incorrect placement or dislodgement, where stabilisation and re-intubation is required.

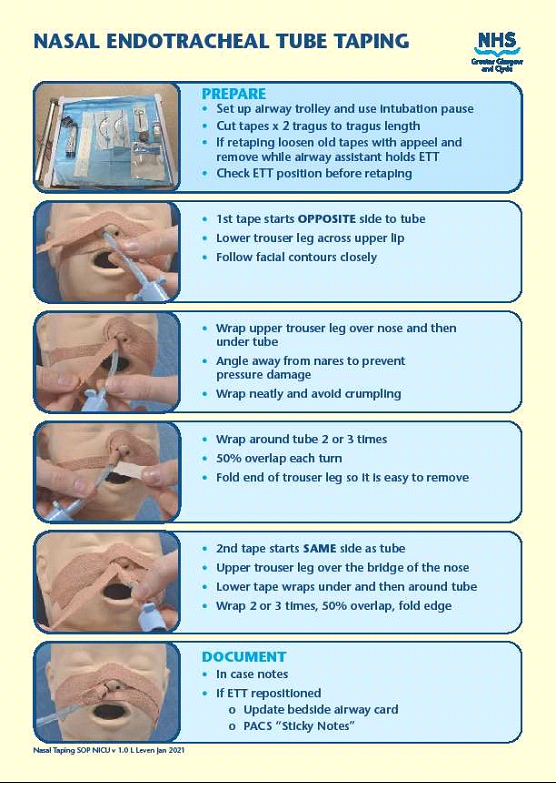

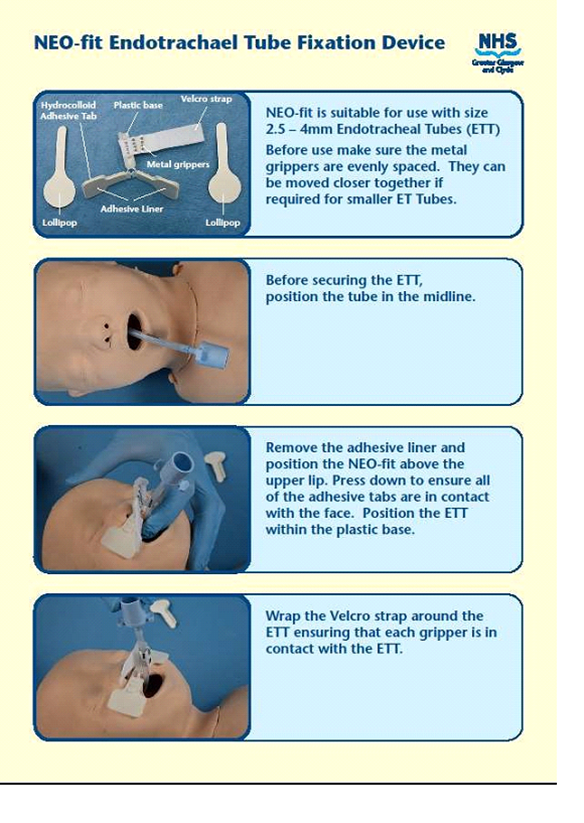

7. ENDOTRACHEAL TUBE FIXATION

Current methods of endotracheal tube fixation include:

- NEO-fit fixation device

- Elastoplast "trouser leg" method

- Neobar

Appendix 2 describes use of the NEO-fit and Elastoplast.

8. POST PROCEDURE

- Chest x-ray is gold standard in confirming correct ETT position, the ET tip should be visible 1cm above carina (T2-T3)

- Consider shortening the ETT to minimise dead space

- Ensure VL blades are sent for sterilisation as per unit protocol

- Ensure accurate documentation of the procedure including the position of the ETT on chest x-ray and whether or not adjustments were made

- Update parents

- If persistent leak >25% AND if interfering with ventialtion, consider upsizing ET tube.

|

Troubleshooting with "DOPE" D - Displaced/Dislodged ETT:

O - Obstruction

P - Pneumothorax

E - Equipment failure

|

2a - nasal and oral tube taping

2b - NEO-fit fixation

NOTE: These video files are held on the NHSGGC Intranet (Staffnet). Your device must have access to the NHSGGC network to view them.

Example 1 - Successful intubation

Good view of the cords, ET successfully inserted, although placed too far into trachea.

Example 3 - Unsuccessful intubation

View of cords seen initially, laryngoscope then slips and view lost

Example 4 - Successful intubation

Note secretions seen but good view of cords so suction not required.

Example 5 - Unsuccessful intubation

Tongue obstructing view and on the wrong side but cords brought into view. ET then inserted into oesophagus.

Example 6 - Successful intubation

Good view of the cords, ET successfully inserted, although placed too far into trachea

- American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Fetus and Newborn, American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Surgery, Canadian Paediatric Society, Fetus and Newborn Committee. Prevention and management of pain in the neonate: an update. Pediatrics. 2006;118(5):2231–2241

- Kumar P et al and Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine. Premedication for Non-emergency Endotracheal Intubation in the Neonate. Pediatrics March 2010, 125 (3) 608-615

- Barrington Premedication for endotracheal intubation in the newborn infant. Paediatr Child Health 2011; 16(3):159–164

- O’Shea J et al. Video Laryngoscopy to Teach Neonatal Intubation: A Randomized Trial. Paediatrics November 2015, 136 (5) 912-919

- O’Shea JE, et al. Analysis of unsuccessful intubations in neonates using videolaryngoscopy recordings. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2018;103:F408–F412

- Kirolos S, O’Shea JE. Comparison of conventional and videolaryngoscopy blades in neonates. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Ed 2020;105:94-97.

- Muniraman HK, Yaari J, Hand I. Premedication Use Before Non-emergent Intubation in the Newborn Infant. Am J Perinatol. 2015 Jul;32(9):821-4

- Lago P. Premedication for non-emergency intubation in the neonate. Minerva Pediatr. 2010 Jun;62(3 Suppl 1):61-3

- E Byrne and R MacKinnon Should premedication be used for semi-urgent or elective intubation in neonates? Dis. Child; Jan 2006; 91: 79 - 83.

- Hodgson KA, Owen LS, Kamlin COF, Roberts CT, Newman SE, Francis KL, Donath SM, Davis PG, Manley BJ. Nasal High-Flow Therapy during Neonatal Endotracheal Intubation. N Engl J Med. 2022 Apr 28;386(17):1627-1637. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116735. PMID: 35476651.

- De Oliveira Flho GR. The construction of learning curves for basic skills in anesthetic procedures: an application for the cumulative sum method. Anesth Analg 2002;95:411-6.

- DeMeo SD, Katakam L, Goldberg RN, et al. Predicting neonatal intubation competency in trainees. Pediatrics 2015;135:e1229–36.

- Wallenstein MB, Birnie KL, Arain YH, et al. Failed endotracheal intubation and adverse outcomes among extremely low birth weight infants. J Perinatol. 2016 ;36:112-5. .

- 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care (Reprint) Part 13: Neonatal Resuscitation Pediatrics November 2015, 136 (Supplement 2) S196-S218

- Blank D, Rich W Leone T, Garey D, Finer N Pedi-cap color change precedes a significant increase in heart rate during neonatal resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2014 Nov;85(11):1568-72

Last reviewed: 04 October 2023

Next review: 04 October 2026

Author(s): Joyce O’Shea – Consultant Neonatologist, RHC, Glasgow; Lynsey Still – Consultant Neonatologist, PRMH, Glasgow

Co-Author(s): Other specialists consulted: Sandy Kirolos – Neonatal Grid Trainee; June Grant – Pharmacist

Approved By: West of Scotland Neonatology MCN