Helicobacter pylori infection in children

exp date isn't null, but text field is

Objectives

This guideline aims to lead to a more consistent clinical practice in the diagnosis and management of Helicobacter pylori in children in the West of Scotland. This guideline is based on the 2016 joint consensus guideline of the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and North American Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN)1 and adapted for use locally.

Scope

This guideline should be followed by all healthcare professionals that are involved in the management of children with H. pylori infection in the West of Scotland.

Audience

Health care professionals working in the West of Scotland, managing patients with possible H. pylori infection.

Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic Gram-negative bacterium that inhabits the mucus layer above the gastric mucosa. The bacterium typically infects the host in early childhood and remains part of the gastric microbiome throughout adult life.2

While 90% of people remain asymptomatic, it is a major source of morbidity and mortality worldwide due to the well-described complications of atrophic gastritis, mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, gastric adenocarcinoma and peptic ulcer disease (PUD).3 H. pylori were classified in the recent Kyoto consensus4 as an infectious disease. Although H. pylori-associated malignancy rarely manifests in childhood, failure to treat correctly exposes the individual to a recognised WHO class I carcinogen. If identified, it is the clinician’s responsibility to ensure eradication with mandatory post-treatment testing.

The natural history in the majority of children is asymptomatic carriage.5 Infection can result in either high, low or neutral gastric acid states depending on the area of the stomach infected and the pathogenicity of the strain.6 In those with hyperacidity in the stomach, symptoms of gastritis or peptic ulcer disease can develop.

H. pylori does not cause gastroesophageal reflux or functional abdominal pain. However, children are often unable to provide precise descriptions of the location and characteristics of pain, so diagnostic delineation on history alone can be challenging. In practice, it is often hard to distinguish between gastroesophageal reflux disease and dyspeptic disease symptoms.

Rates of antibiotic-resistant H. pylori have rapidly increased over the past 20 years corresponding to a decline in the efficacy of standard treatment regimens.1 Responsible antibiotic stewardship by careful selection of the most effective treatment regimen is essential to maintain treatment effectiveness.

Aims of assessment and treatment

- Test only when there is an indication

- Use an appropriate test

- Use the best possible first-line treatment regimen

- Confirm eradication

H. pylori infection rarely causes symptoms in children in the absence of peptic ulcer disease. Symptomatic children should be tested to diagnose the cause of specific symptoms rather than simply identify H. pylori.7 Further evaluation should be reserved for when epigastric pain is closely associated with the intake of food or when there are associated ‘red flag’ features (Table 1). Testing is not indicated for suspected functional abdominal pain or gastroesophageal reflux disease. Parents should be counselled that, in the absence of PUD, eradication may not relieve symptoms however is still probably required to reduce the carcinogen risk. We do not currently advocate for routine tolerance of detected H. pylori given the “known carcinogen” status of the organism, but this is an active debate within the literature and the position may shift with time.

Table 1: Symptoms of PUD and ‘red flag’ features in GI disease

|

Symptoms associated with Gastritis/PUD |

GI Red Flag Symptoms (not necessarily H. pylori-related) |

|

Haematemesis or melaena Localised epigastric pain

|

Localised epigastric pain |

Special Situations

- Testing in patients with functional abdominal pain or gastroesophageal reflux is not recommended

- Iron deficiency anaemia is no longer an indication for testing

- There is no evidence that testing and treating family members for H. pylori infection reduces the risk of reinfection

- A family history of gastric cancer is no longer an indication for testing

- Patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura should be considered for testing

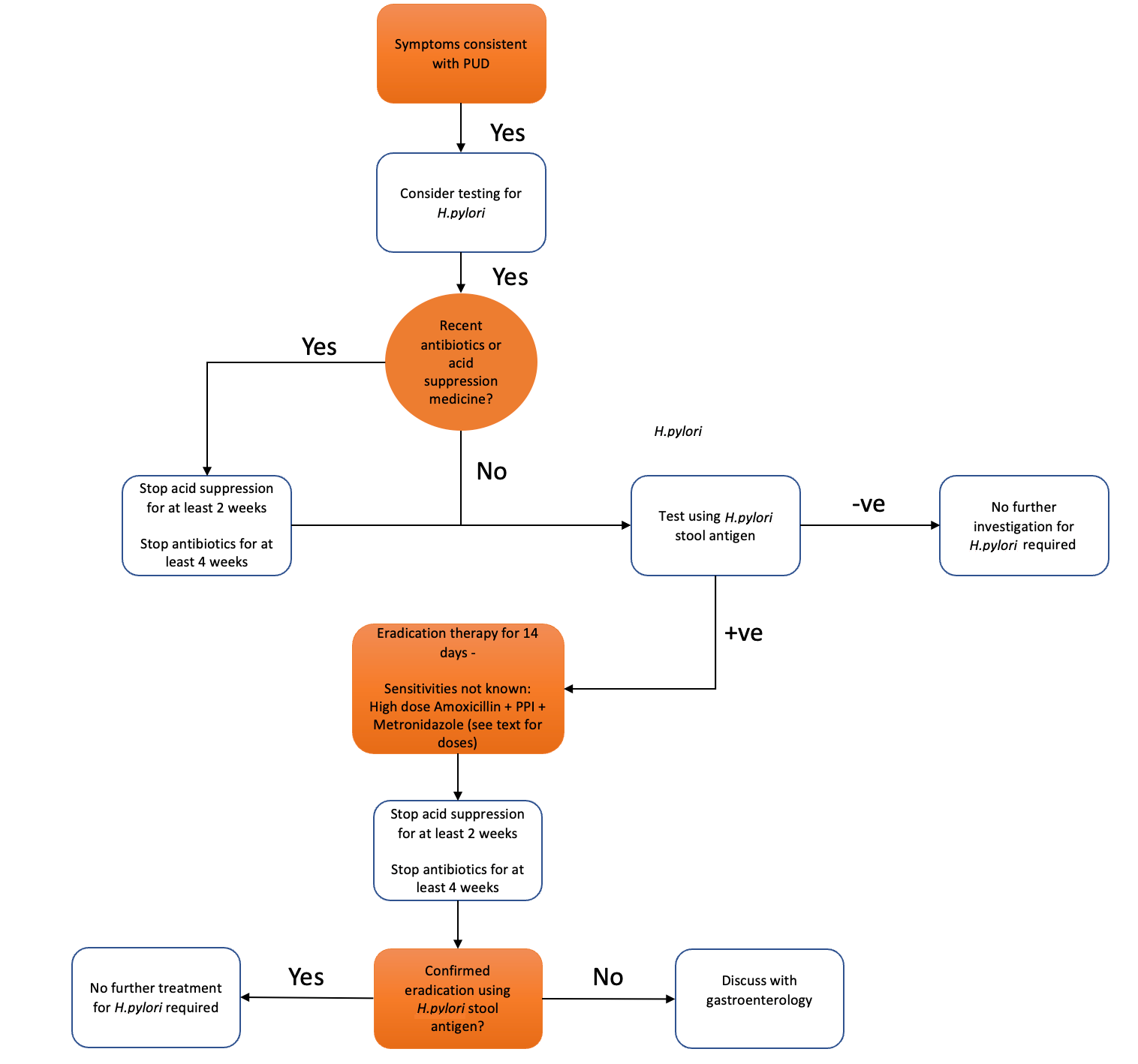

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with biopsy for histology is the recommended gold standard, largely because of its ability to formally diagnose PUD and so help stratify acid suppressant treatment thereafter. Pragmatically, however, the balance of general anaesthetic risk and procedural expense means a great many children could be spared endoscopy with a simpler first-line approach. We therefore recommend first-line diagnosis based on stool antigen testing, followed by eradication if positive. Children should only be referred for gastroenterology opinion and endoscopy when they have failed to have a successful primary eradication of H. pylori confirmed by a positive repeat stool antigen test.

Our recommendation would be to use stool antigen testing for both the initial diagnosis of H. pylori infection and for confirmation of eradication.

Patients should be off acid suppression for at least two weeks and antibiotics for four weeks before testing. The use of Gaviscon preparations should not affect test results.

Acid suppression inhibits the growth of H.pylori therefore will result in a higher false negative rate. A negative test on acid suppression should be repeated. A positive test on acid suppression should be considered genuine.

Note:

- Non-invasive tests: stool antigen testing is as reliable as the urease breath test and is much easier to do in younger patients.

- Blood-based serology tests are NOT reliable for use in routine paediatric practice (their use in adults is pragmatic based on the high use of acid suppressants and the difficulty with other investigations in this setting).

Rising antibiotic resistance means it is essential to maximise the success of first-line treatment regimens. Compliance is key and should be carefully discussed and reinforced with families; the high eradication rates with recommended treatment regimens rely on >90% compliance (<3 doses missed in a 14-day regimen). A twice-daily dosing regimen is given to maximise compliance. 14-day regimens are now recommended due to increased efficacy above 10- and 7-day regimens. Ideally, antibiotic choice would be based on culture and sensitivity though this is impractical in the majority of cases. Molecular biopsy-based techniques or stool PCR may be used in the future to identify antibiotic-resistant strains before choosing antibiotics, however this is not currently the standard of care.

First-Line Treatment Regimen

For patients where the antibiotic sensitivity and resistance patterns are not known (the majority of non-biopsied patients) our recommendation is triple therapy for 14 days with:

Omeprazole, HIGH DOSE amoxicillin and metronidazole

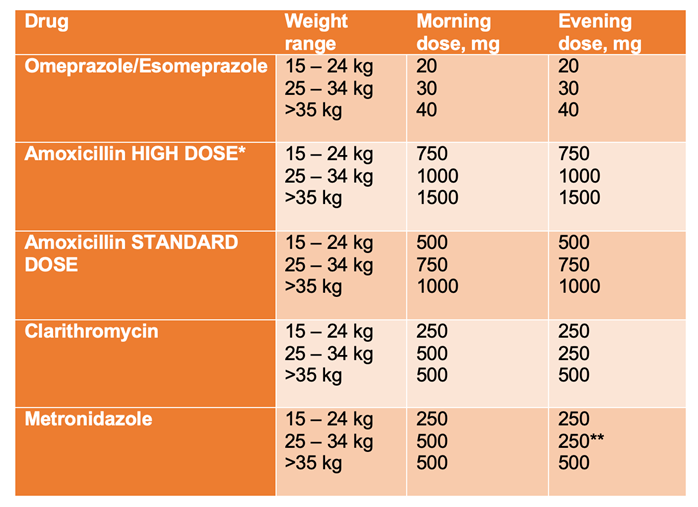

The doses recommended are given below and are given in the ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN H. pylori Guidelines (reference below). If asking GP to prescribe these doses, a reference may be required due to deviation from the BNFc. Higher dose PPI improves treatment success. Where peptic ulcer is strongly suspected, 3 months of acid suppression should also be used to promote healing.

Table 2: Recommended medication doses based on the ESPGHAN H.pylori guidelines1

HIGH DOSE recommended as the first line when antibiotic sensitivities are not known (most cases)

** If oral suspension of metronidazole is employed, the dose can be divided to be equal every 12 hours

Second-Line Treatment Regimen

To maximise treatment effectiveness, second-line treatment should be discussed with your local gastroenterology team

Patients who have previously taken clarithromycin and/or metronidazole should be considered at high-risk for resistance.

Confirmation of eradication

- The long-term risk and uncertainty regarding gastric carcinoma mean confirmation of eradication is MANDATORY.

- Eradication of H. pylori infection should be confirmed 4-8 weeks after treatment using stool antigen testing.

- Patients should be off acid suppression for at least two weeks and antibiotics for four weeks before testing – peptic ulcer patients should complete their 3-month acid suppression course before confirming eradication.

Referral to Gastroenterology

Patients with H. pylori should be referred for opinion and endoscopy when they have failed to have a successful eradication with confirmatory positive post-treatment stool antigen test.

Persistence of dyspeptic symptoms after a trial of appropriately dosed acid suppression or dependence on long-term acid suppressants with/without H. pylori are further indicators for consideration of endoscopy.

- Jones NL, Koletzko S, Goodman K, et al. Joint ESPGHAN/NASPGHAN Guidelines for the Management of Helicobacter pylori in Children and Adolescents (Update 2016). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64(6):991-1003. doi:10.1097/MPG.0000000000001594

- Rowland M, Daly L, Vaughan M, Higgins A, Bourke B, Drumm B. Age-specific incidence of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(1):65-72. doi:10.1053/J.GASTRO.2005.11.004

- Moodley Y, Linz B, Bond RP, et al. Age of the association between Helicobacter pylori and man. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(5). doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PPAT.1002693

- Sugano K, Tack J, Kuipers EJ, et al. Kyoto global consensus report on Helicobacter pylori gastritis. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309252

- Hansen R, Russell RK, Muhammed R. Recent advances in paediatric gastroenterology. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2014-307089

- Pariente B, Cosnes J, Danese S, et al. Development of the Crohn’s disease digestive damage score, the Lémann score. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17(6):1415. doi:10.1002/IBD.21506

- Wands DIF, El-Omar EM, Hansen R, Gastroenterology P. Helicobacter pylori: getting to grips with the guidance Education. Gastroenterology. 2021;12:650-655. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2020-101571

Last reviewed: 17 July 2023

Next review: 31 May 2026

Author(s): Wands D, Sullivan A, Morrison K, Bland R, Hansen R

Author Email(s): David.wands4@ggc.scot.nhs.uk

Approved By: RHC GI & Paediatric Departments

Document Id: 1096