Nurse Led blind Insertion of naso jejunal tube in PICU

exp date isn't null, but text field is

Objectives

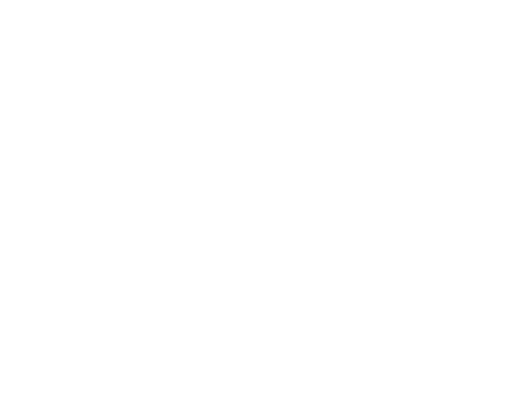

- To provide a clear rationale for the blind insertion of jejunal tubes in critical care

- To provide procedural guidance on the blind bedside placement technique for jejunal feeding tubes within paediatric critical care.

- To ensure that recommendations from recent patient safety notices are adhered to (NPSA, 2011 and 2012)

This guideline should be interpreted in conjunction with the NHSGGC PICU Guideline on Administration of Medication via Enteral Feeding Tubes (2012) and NHSGGC PICU Guideline for Introducing and Establishing Enteral Nutrition in PICU (2016).

Scope

This guideline applies to all patients in paediatric critical care (PICU/HDU). (Exclusion criteria are outlined in the procedure algorithm).

Audience

All healthcare professionals in paediatric critical care involved in the blind insertion of jejunal feeding tubes should be familiar with this guideline.

Optimal provision of nutrition support and accurate assessment of energy expenditure should be an integral component of paediatric critical care (Mehta et al, 2009a). Nutritional status has a profound effect on metabolic response to injury and strongly affects patient outcome (Mitchell et al, 1994) including length of ventilated days and PICU stay (Larsen et al, 2008).

Providing nutritional care in critically ill children is challenging since fluid restrictions, digestive intolerance and interruptions in nutritional feed delivery for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures are common (Lambe et al, 2007) and result is a failure to deliver estimated energy requirements (Cohen et al 2000 and de Neef et al, 2007). With no commonly accepted guidelines for nutritional management in PICU available (Van der Kuip et al, 2004) and a lack of systemic research and clinical trails in PICU, compiling evidence based guidelines is challenging (Mehta et al, 2009b).

Elevated gastric residual volumes (GRV) are associated with sedation and catecholamine use (Mentec et al, 2001) and in paediatric patients are often attributed to gastric paresis. Although, McClave et al (2005) state that GRVs are inherently flawed, as they have yet to be validated, current paediatric evidence suggests that a GRV > 5ml/kg can be considered to be an indicator of poor feed tolerance and delayed gastric emptying (Cobb et al, 2004 and Horn et al, 2004).

A number of studies in adult patients have advocated the use of prokinetics to aid gastric motility (Cohen et al, 2000 and McClave et al 2005) however, no studies have analysed the efficacy of prokinetics in critically ill children (Lopez-Herce, 2009). It is therefore, advocated not to delay commencement of jejunal feeding in those with delayed gastric emptying in order to trial prokinetics. This is supported by a study by Gharpure et al (2001) which concluded erythromycin did not facilitate post-pyloric tube placement.

Enteral nutrition is always the preferred route for artificial feeding in critically ill children and naso-jejunal feeding offers a safe and effective alternative to parenteral nutrition for patients, in whom gastric feeding is poorly tolerated, including post-op cardiac patients (McDermott et al, 2007 and Sachez et al, 2006). Unlike gastric feeding, jejunal feeding avoids fasting times for many procedures, including endotracheal extubation thereby, ensuring energy delivery and reducing the risk of protein energy malnutrition (Jacobs et al, 1999).

Jejunal tubes have traditionally been avoided as they have been notoriously difficult to place, often requiring endoscopic or radiological guidance (Meyer et al, 2007). However, blind placement techniques have now been shown to be up to 95% successful within the PICU population (Joffe et al, 2000, Spalding et al, 2000 and Meyer et al 2007), with associated benefits to patient outcome and financial savings for health care authorities.

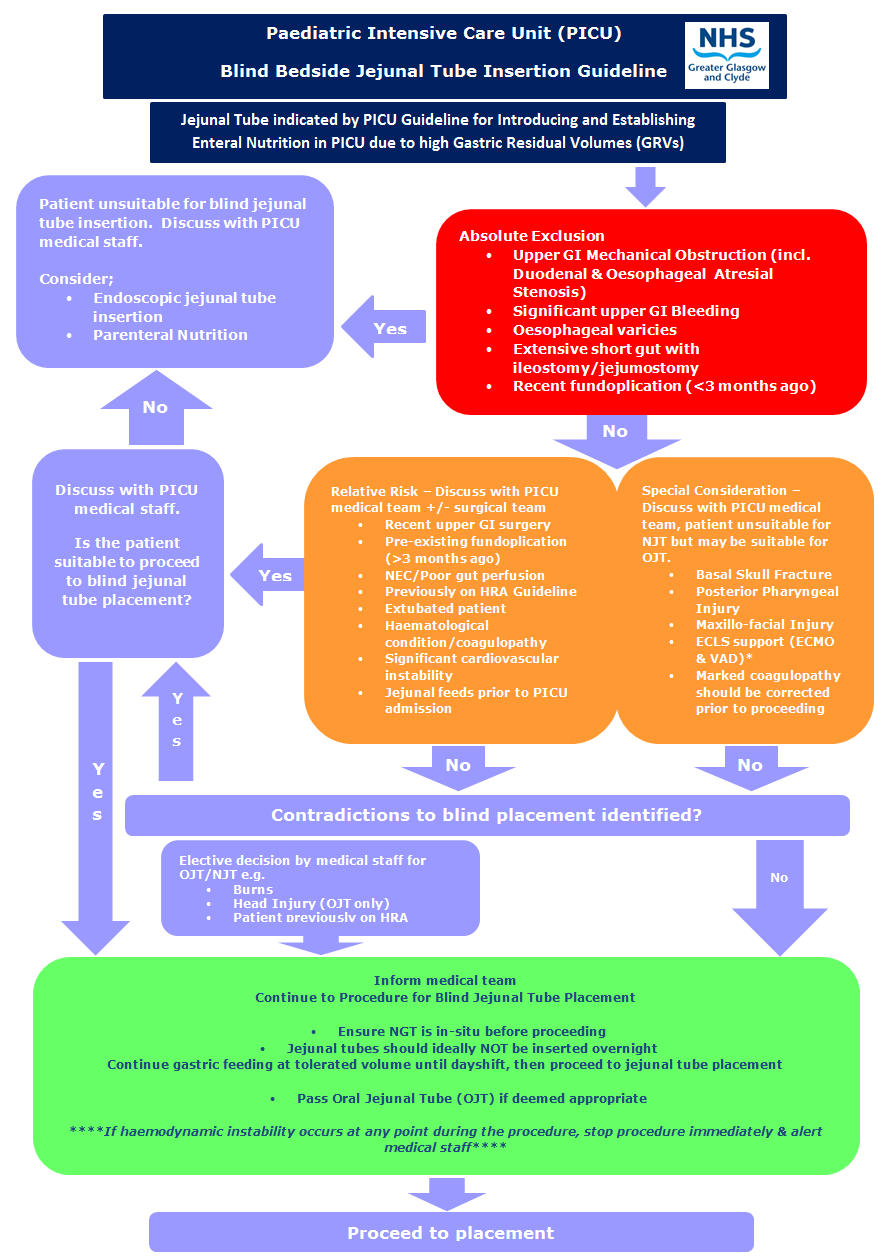

1) EQUIPMENT and INITIAL PROCEDURE

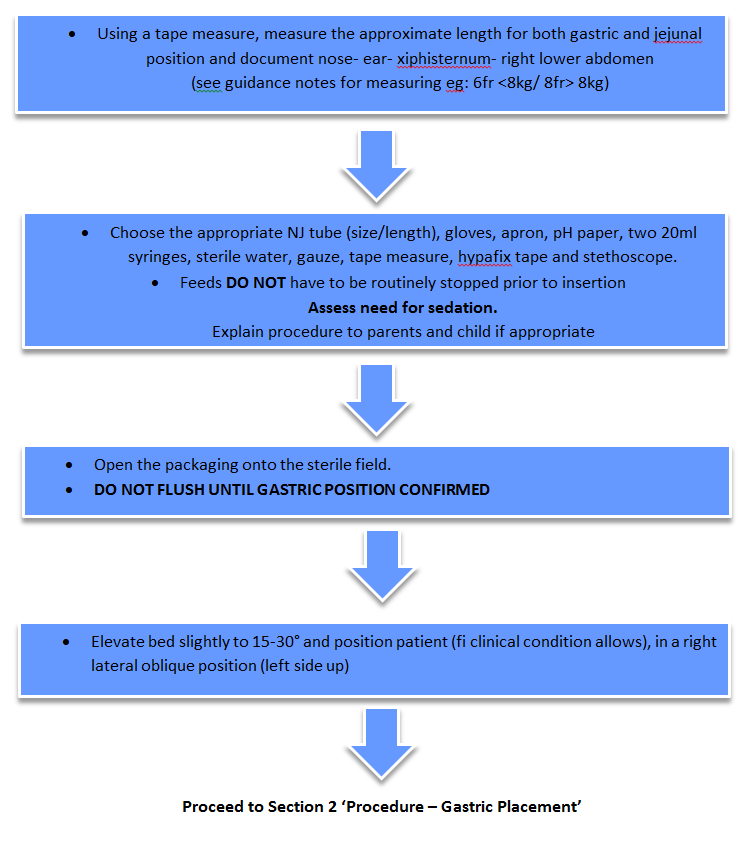

2) Procedure - Gastric Placement

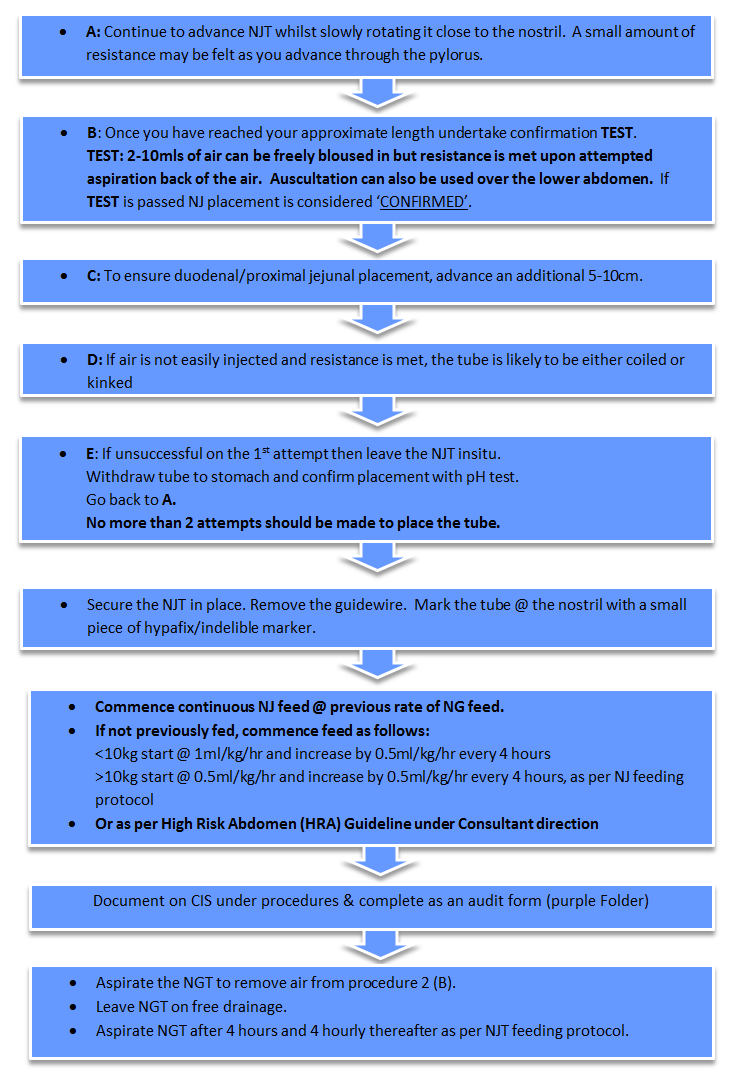

3) PROCEDURE - JEJUNAL PLACEMENT

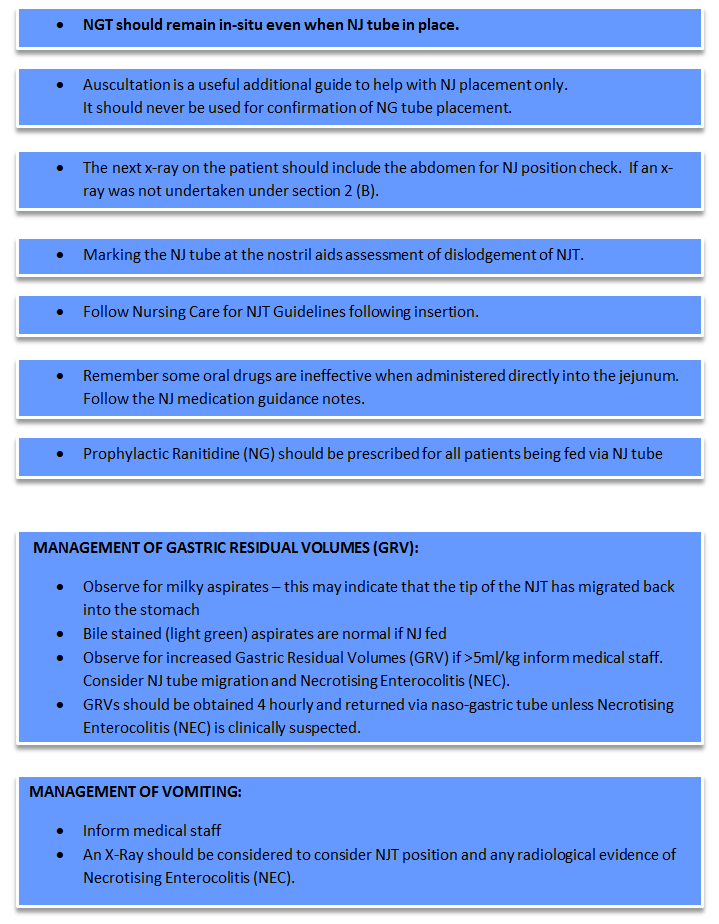

4) General Notes

Figure 1: Nasojejunal tube length measurement

Notes:

- Measurement should be made using a disposable tape measure

- Measure from nose – ear – xiphisternum – right lower abdomen (right iliac crest)

- Note measurement at xiphisternum and right lower abdomen

- Use a Merck Corflo NJ tube with guidewire of appropriate length. If <8kg use 6Fr, >8Kg use 8Fr, older children may require a 10Fr.

CARE OUTCOMES:

- To maintain nutrition and hydration

- To prevent potential complications – tube blockage, tube misplacement, aspiration and accidental removal

|

Nursing care |

Rationale |

|

1. Ensure procedure documentation is completed on CIS, including the insertion date, the size and internal length of the NJ tube.

|

To prevent infection To prevent displacement |

|

2. Every 4 hours document on CIS the external length of the NJ tube and ensure tube is securely taped. |

To prevent displacement

|

|

3. Every 4 hours aspirate Naso-gastric tube and test pH as per nasogastric feeding guideline. If milk aspirated, it is probable that NJ tube has migrated back into the stomach, follow the NJ feeding guideline. If no aspirate obtained follow naso-gastric tube feeding guideline. * If NJ tube displacement is suspected (eg. following extubation or vomiting), the following test can be used to confirm placement:

a) If a high volume of air is aspirated (>15ml) NJ tube is likely to be in oesophagus or upper part of stomach. b) If a high volume of secretions (>15ml) NJ tube likely to be in stomach and test pH = 1-4. NB. Drugs such as Ranitidine, Omprezole & Sucralfate will increase gasric pH. If the test is not conclusive seek medical advice. A check X-ray of chest/abdomen maybe required. |

To prevent displacement, aspiration and accidental removal.

To maintain nutrition and hydration.

|

|

4. Strict hand washing is essential. Clean the feeding end with alcohol swabs. |

To prevent infection as the NJ tube bypasses the stomach’s anti-infective acid. |

|

5. Pre-packed feeds can be hung for 24 hours. Prepared feeds (and feeds with active ingredients) should be changed every 4 hours and all feeding sets every 24 hours using a non-touch technique. |

To prevent infection as the NJ tube bypasses the stomach’s anti-infective acid. |

|

6. Feeds and most drugs are given via the NJ tube. Follow the NJ feeding guideline for type of feed and build up flow rates. Continuous feeds only via NJ tube.

|

Bolus feeds must not be given through the naso-jejunal tube because the jejunum cannot hold a bolus and it causes abdominal pain, diarrhoea and dumping syndrome. |

|

7. Most medications should be given via the NJ tube. Follow the guideline for NJ medication. NB: flushing with sterile water. |

To prevent blockage. To prevent reaction with feed and between drugs. |

|

PROBLEM SOLVING |

RATIONALE |

|

Feed Intolerance

|

Diarrhoea may be caused by feed rate being increased too quickly. Vomiting may be caused by NJ tube migrating into stomach. |

|

Blocked Tube

|

Warm water may dissolve fatty deposits on the tube. Pancreatic enzymes (Creon) digest the build up of feed on the internal lumen of the NJ tube. Sodium Bicarbonate dissolves the coating on the granules and activates the pancreatic enzymes. NJ tube should only be placed by a nurse trained to do so. |

|

Displacement of Tube

|

To reposition tube in to the correct position for use. To replace the tube. NJ tube should only be placed by a nurse trained to do so |

References for nursing guideline

Harrison AM et al (1997) Non-radiological assessment of enteral feeding tube position. Critical Care Medicine. 25 2055-2059.

Joffe A, Grant M, Wong B, Gresuik C (2000) Validation of a blind transpyloric feeding tube placement technique in paediatric intensive care: rapid, simple, and highly successful. Paediatric Critical care Medicine. 1(2) 151-155.

Meyer R, Harrison S, Cooper M, Habibi P (2007) Successful blind placement of nasojejunal tubes in paediatric intensive care: impact of training and audit. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 60(4) 151-155.

McDermott A, Tomkins N, Lazonby G (2007) Nasojejunal tube placement in paediatric intensive care. Paediatric Nursing. 19(2) 26-28.

Sachez C, Lope-Hence J, Carrillo A, Bustinza A, Sancho L and Dolores V (2006) Transpyloric enteral feeding in the postoperative of cardiac surgery children. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 41 1096-1102

Spalding HK, Sullivan KJ, Soremi O, Gonzalez F, Goodwin SR (2000) Bedside placement of transpyloric feeding tubes in the paediatric intensive care unit using gastric insufflation. Critical Care Medicine. 28(6) 2041-2044.

NHS QIS (2007) Caring for children & young people in the community receiving enteral tube feeding. Best Practice Statement. NHS Quality Improvement Scotland.

Other References

Babbitt, C. (2007) Transpyloric feeding in the pediatric intensive care unit. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 44(5): 646-9.

Cobb BA, Waldemar CA and Ambalavanan N (2004) Gastric residuals and their relationship to necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 113 (1) 50-53.

Cohen J, Aharon A and Singer P (2000) The paracetamol absorption test: a useful addition to the enteral nutrition algorithm? Clinical Nutrition 19 (4) 233-236.

Da Silva PS, Paulo CS, de Oliveira Iglesias SB et al. (2002) Bedside transpyloric tube placement in the pediatric intensive care unit: a modified insufflation air technique. Intensive Care Medicine, 28(7): 943-6.

De Lucas C, Moreno M, Lopez-Herce et al. (2000) Transpyloric enteral nutrition reduces the complication rate and cost in the critically ill child. J Pediatric Gastroenterol Nutr. 30(2): 175-80.

de Neef M, Geukers VGM, Dral A, Lindeboom R, Sauerwein HP and Bos AP (2008) Nutritional goals, prescription and delivery in a pediatric intensive care unit. Clinical Nutrition 27 65-71.

Gharpure V, Meert KL and Sarnaik AP (2001) Efficacy of erythromycin for postpyloric placement of feeding tubes in critically ill children: a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 25 (3) 160-165.

Horn D, Chaboyer W and Schluter PJ (2004) Gastric residual volumes in critically ill paediatric patients: A comparison of feeding regimens. Australian Critical Care 17 (3) 98-103.

Jacobs B, Richard B, Lyons K and Wieman R (1999) Transpyloric feeding during ventilatory weaning and tracheal extubation is safe and effective in children. Critical Care Medicine 27 (1) supplement p159A.

Joffe A, Grant M, Wong B and Gresiuk C (2000) Validation of a blind transpyloric feeding tube placement technique in pediatric intensive care: rapid, simple, and highly successful. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 1 (2) 151-155.

Krafte-Jacobs B, Persinger M, Carver J. (1996) Rapid placement of transpyloric feeding tubes: a comparison of pH-assisted and standard insertion techniques in children. Pediatrics, 98(2 Pt 1): 242-8.

Lambe C, Hubert P, Jouvet P, Cosnes J and Colomb V (2007) A nutritional support team in the pediatric intensive care unit: Changes and factors impeding appropriate nutrition. Clinical Nutrition 26 355-363.

Larsen B Goonewardene L, Joffe AR, Van Aerde J, Field CJ and Clandinin MT (2008) Energy intake significantly affects hospital outcomes in infants after open heart surgery. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 32 (3) 317.

Lazonby GM, Mc Dermott AR, Haywood T (2004) PICU Guideline for Bedside Nasojejunal Tube Placement without Drugs or X-Rays. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition, 39(1): 494.

Lopez-Herce (2009) Gastrointestinal complications in critically ill patients: what differs between adults and children. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 12 180-185.

McClave SA, Lukan JK, Stefater JA, Lowen CC, Looney SW, Matheson PJ, Gleeson K and Spain DS (2005) Poor validity of residual volumes as a marker for risk of aspiration in critically ill patients. Critical Care Medicine 33 (2) 324-330.

McDermott A, Tomkins N and Lazonby G (2007) Nasojejunal tube placement in paediatric intensive care. Paediatric Nursing 19 (2) 26-28.

Mehta N, Compher C and ASPEN Board of Directors (2009b) ASPEN Clinical Guidelines: Nutrition Support of the Critically Ill Child. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 33 (3) 260-276.

Mehta NM, Bechard LJ, Leavitt K and Duggan C (2009a) Cumulative energy imbalance in the pediatric intensive care unit: role of targeted indirect calorimetry. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 33 (3) 336-344.

Mentec H, Dupont H, Bocchetti M, Cani P, Ponche F and Bleighner G (2001) Upper digestive intolerance during enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: frequency, risk factors, and complications. Critical Care Medicine 29 (10) 1955- 1961.

Meyer R, Harrison, S, Cooper M and Habibi, P (2007) Successful blind placement of nasojejunal tubes in paediatric intensive care: impact of training and audit. Journal of Advanced Nursing 60 (4) 402-408

Mitchell IM, Davies PSW, Day JME, Pollock JCS, Jamieson MPG (1994) Energy expenditure in children with congenital heart disease, before and after cardiac surgery. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 107 (2) 374-380.

NPSA National Patient Safety Agency (2011) Reducing the harm caused by misplaced nasogastric feeding tubes in adults, children and infants. NPSA/2011/PSA002 10 March 2011.

NPSA National Patient Safety Agency (2012) Rapid Response Report: Harm from Flushing of Nasogastric Tubes before Confirmation of Placement. NPSA/2012/RRR001 22 March 2012.

Phipps, L.M., Weber, M.D., Ginder, B.R., et al. (2005). A randomized controlled trial comparing three different techniques of nasojejunal feeding tube placement in critically ill children. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, 29(6), 420-4.

Porter M, Knapp L, Cooper D, et al. (2005) Transpyloric feeding tube placement in critically ill children. Critical Care Medicine. 33 (12 Suppl): A21.

Sachez C, Lope-Hence J, Carrillo A, Bustinza A, Sancho L and Dolores V (2006) Transpyloric enteral feeding in the postoperative of cardiac surgery children. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 41 1096-1102.

Spalding HK, Sullivan KJ, Soremi O, Gonzalez F and Goodwin SR (2000) Bedside placement of transpyloric feeding tubes in the pediatric intensive care unit using gastric insufflation. Critical Care Medicine 28 (6) 2041-2044.

Van der Kuip M, Oosterveld MJS, Van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MAE, Lafeber HA and Gemke RJBJ (2004) Nutritional support in 111 pediatric intensive care units: a European survey. Intensive Care Medicine 30 1807-1813.

Last reviewed: 24 November 2020

Next review: 30 November 2023

Author(s): Isobel Macleod

Co-Author(s): Susan Greenock, Neil Spenceley, Mark Davidson, Jackie Mara, Emma Gentles

Approved By: Paediatric Clinical Effectiveness & Risk Committee